After his mother was murdered when he was 14, Chris Tucker could not stop thinking about death. He wanted to die himself. Or he envisioned killing the perpetrator. He could hardly sleep and was struggling at school.

It was not until he met a social worker on campus in Schertz, east of San Antonio, that Tucker began to see a path forward through the grief. They talked, and he later agreed to participate in a summer program where he opened up about his experience and formed a community.

“We’ve grown and reshaped ourselves to be the people that we really wanted to be,” said Tucker, now 26 and an accountant in Philadelphia.

THE AFTERMATH: After Uvalde massacre, Texas GOP leaders double down on the same fixes they tried after Santa Fe

Tucker’s was the kind of positive outcome state lawmakers pictured in 2019, when they worked to increase mental health resources for students after the mass shooting at Santa Fe High School that left eight students and two teachers dead.

Access to those services again is at the forefront as Republican leaders respond to last week’s massacre in Uvalde.

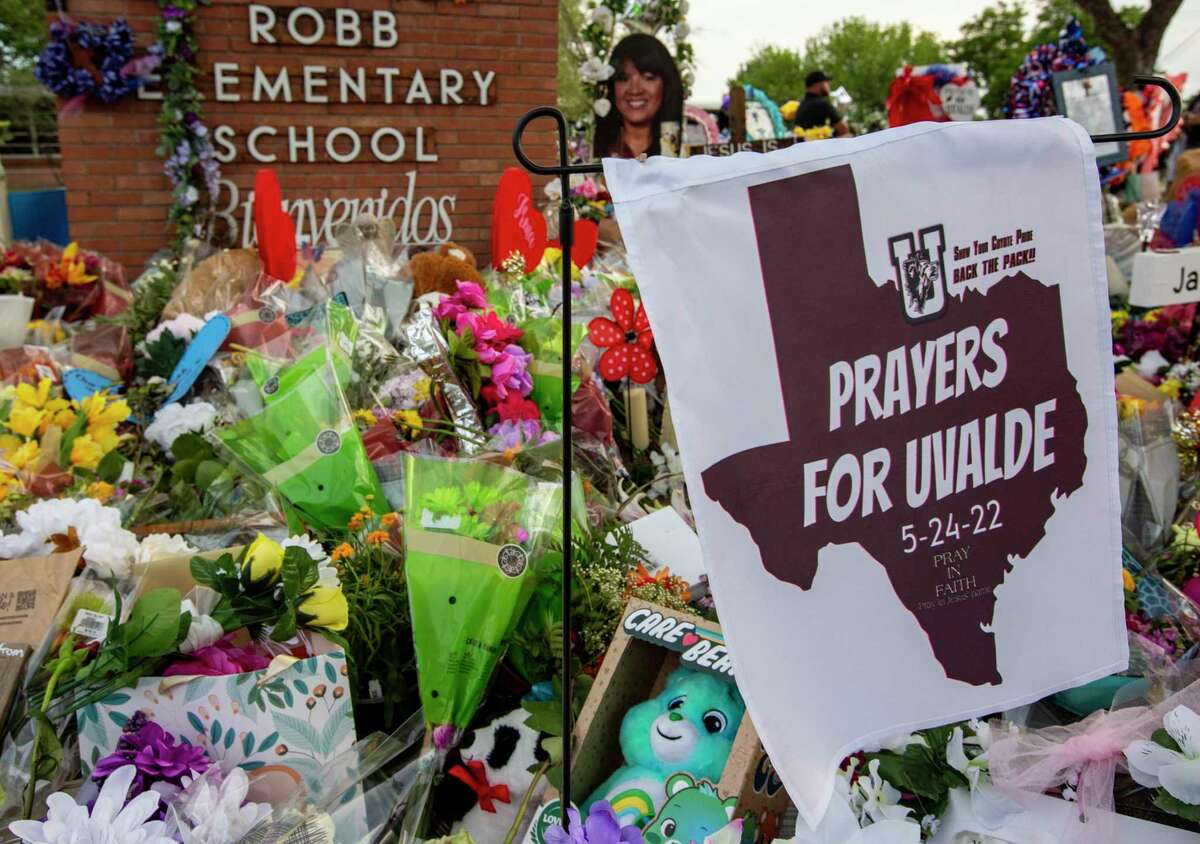

Genevieve Tijerina, 11, uses chalk to write “We Will Rise” on the ground at the Town Square, the site of a memorial for the victims of the mass shooting at Robb Elementary School, on Friday, May 27, 2022, in Uvalde, Texas.

Godofredo A. Vásquez, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographerMental health experts say the 2019 initiatives, including hundreds of millions of dollars more in funding, have only begun to address Texas’ mental health crisis, and that the state does little to track even their limited outcomes. Many school districts are left to fund their own interventions.

There is little evidence that mental illnesses cause mass shootings or that people diagnosed with them are more likely to commit violent crimes. Advocates also warn that scapegoating mental illness can stigmatize the wide spectrum of people living with psychological disorders.

“It’s absolutely something that should be addressed — but it’s not a panacea,” said Greg Hansch, executive director for the Texas chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. “It’s more of a secondary or tertiary factor.”

Gov. Greg Abbott and other top Republicans have pointed to the shortage of mental health resources, especially in rural Texas, as a key factor in the Uvalde shooting, while rejecting calls for stricter gun laws.

The makeshift memorial in front of Robb Elementary School is seen Tuesday, May 31, 2022 in Uvalde one week after 19 children and two adults were killed at the school May 24, 2022 by a gunman with an assault rifle.

William Luther, StaffThe 18-year-old gunman, who killed 19 children and two adults, legally purchased the assault-style weapon he used in the shooting spree and had “no known mental health history,” Abbott said.

Even with the 2019 reforms, mental health care remains vastly underfunded in Texas. That largely is because of budget cuts two decades ago and years of stagnant funding to community mental health services. Today, Texas provides less access to care than any other state, and nearly three quarters of children and teenagers with major depression do not get treated, the highest rate in the country, according to the nonprofit group Mental Health America.

Without a direct source of state funding for mental health care, school districts in Texas are forced to rely on a patchwork of state and federal programs, most of which do not guarantee that money will flow to mental health services for students or training for teachers. As a result, only a tiny fraction of Texas’ roughly 1,200 public school and open-enrollment charter districts have enough counselors, social workers and psychologists to meet professionally recommended student-to-provider ratios, according to a recent Houston Chronicle analysis.

Lessons from Santa Fe

Central to lawmakers’ 2019 response was a new mental health consortium overseen by the University of Texas System, with a $99 million initial investment for programs focused on children and teens, including virtual visits between child psychologists and students referred by school staff. The Legislature also increased funding to Communities in Schools, which places staff directly on campuses and had employed Tucker’s social workers.

In addition, lawmakers required school officials to form “threat assessment teams” to identify students who may pose a risk of violence, and put forth another $100 million to school districts every two years that can be used to hire security personnel, provide mental health services and buy physical upgrades, such as metal detectors and bullet-resistant glass.

In the first year, however, just 12 percent of Texas school districts reported using any of the funds for mental health support, while 8 percent said the money was used for behavioral health services, according to a survey by the Texas School Safety Center at Texas State University.

A task force later found the Texas Education Agency was not collecting meaningful data on mental health programs in schools, including the number of students they serve or “any standard outcomes” they measure. The Legislature responded with a bill last year to bolster reporting, but the agency has yet to release any results.

FORMER COP SHOT IN SANTA FE: Increase security or let parents, teachers protect themselves

Annalee Gulley, director of public policy and government affairs for Mental Health America of Greater Houston, said lawmakers have taken encouraging steps to support mental health but should have paired the funding with more direction for school officials on how to spend it.

“A critical lesson learned in the years following the Santa Fe High School shooting is funding alone is not enough,” Gulley said. “Instead, the state must connect financial resources to guidance on the most effective strategies to support the safety and well-being of educators and students following such a catastrophic event.”

Much of the focus since 2019 has been on the telehealth effort known as TCHATT, including more than $50 million in added pandemic funding last year. The program has been slow to expand, however, serving only about 6,000 students so far. By comparison, Communities in Schools serves 115,000 students annually on a $35 million budget. There are more than 5 million students in Texas.

Neither Communities in Schools or TCHATT was present in Uvalde, though counselors and social workers have been pouring into the city since last week and plan to be there throughout the summer. Other consortium programs, including one that trains primary care doctors to treat mental health issues in young patients, have been slowed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We’re on the right path, but we’ve still got a lot of work to do,” said David Lakey, who heads the mental health consortium and is vice chancellor for health affairs at the University of Texas System.

Lakey previously led the Texas Department of State Health Services and is a medical doctor. From a public health standpoint, he said, mental health is one of several issues that need attention after Uvalde, as well as school safety measures and gun control.

“I understand people have differences of opinion, but I think a lot of people are re-looking at, call it gun safety or other things,” Lakey said, speaking in his personal capacity.

Sarah Wakefield, who chairs the psychiatry department at the Texas Tech Health Sciences Center and created one of the early models for TCHATT, said the program is intended to assess students who are struggling and pair them with the appropriate long-term intervention, such as community mental health programs or with participating pediatricians.

“The goal is to say, hey, we’ve done a really clear diagnostic assessment, we have figured out why you’ve been struggling, we know what you’re responding to and what’s going to be effective,” Wakefield said.

Competition for specialists

Since Uvalde, Abbott and other state leaders have signaled plans to again ramp up spending on mental health care and other areas they believe will help prevent school shootings. At the governor’s request, Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick and House Speaker Dade Phelan this week assigned committees in each chamber of the Legislature to study existing school safety laws and recommend new policies related to mental health, social media, police training and firearm safety.

Hansch recommended lawmakers also consider directly funding mental health services in schools, perhaps by requiring districts to put a minimum amount of the school safety funds they now receive from the state toward mental health.

Some school districts have used the federal dollars made available for pandemic relief to expand counseling and mental health services, but hiring is difficult for positions requiring more specialized degrees and licensing.

San Antonio ISD, for example, has tried to add social service providers to every one of its nearly 100 campuses, including people who can provide clinical counseling and psychological services to backstop its 147 guidance counselors.

People line up to pay their respects at a memorial at Robb Elementary School, in Uvalde, Texas, Sunday, May 29, 2022. On Tuesday, 21 people, including 19 students, were killed in a mass shooting.

Jerry Lara / San Antonio Express-NewsSAISD partners with Communities in Schools of San Antonio to fill the majority of these roles, and is looking to hire 20 more social service providers through the nonprofit.

Northside ISD used its partnership to add social work services and mental health support and increased its hiring in-house. It and other larger area districts expected to fill a relative handful of counselor vacancies without much problem.

“School counselors in Texas are really the first line of mental health services at a public school campus,” said Mary Libby, Northside ISD’s director of guidance.

Some smaller districts have had a more difficult time competing for counselors. South San Antonio ISD still is trying to hire two “at risk” counselors for middle schoolers. Before 2020 it had just one counselor serving more than 450 middle school students. When the pandemic hit, it needed more, to help students struggling from isolation, grief and stress, said Charlie Gallardo, the director of guidance and counseling.

“It is discouraging,” Gallardo said. “But I understand. You look around, there are counselor openings everywhere.”

Staff writers Danya Perez and Claire Bryan contributed to this report.