Underserved communities in Philadelphia face many barriers to receiving medical care, a persistent issue that has contributed to a lengthy list of inequities – from maternal health outcomes to insurance access.

In an effort to address polices and practices that have hampered these communities, the Independence Blue Cross Foundation has created the Institute for Health Equity through a five-year, $15 million investment.

The institute initially will focus on digital health, cultural competence in medicine and maternal health.

Gregory Deavens, president and CEO of Independence Blue Cross, said it’s necessary for health care organizations to invest in inclusive innovation aimed at improving the health of everyone.

“There are unacceptable disparities in health care access and outcomes, and we can’t wait any longer to address these conditions,” Deavens said. “The impact on people’s lives and livelihoods are critically important and require immediate action.”

Philadelphia has consistently fared poorly in the annual County Health Rankings put out by the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In the latest edition, Philly ranked last among the 67 Pennsylvania counties in health outcomes – defined as how long residents live and how healthy they are.

Disparities in maternal health are particularly glaring.

Across the U.S., Black women are more than three times more likely to die in pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum year than white women. And this gap persists across all incomes and education levels.

In Philadelphia, a disproportionate amount of Black women die in childbirth compared to white women. Between 2013 and 2018, 73% of the deaths related to pregnancy occurred among Black women, despite the fact that they only accounted for 43% of live births during that time period.

A Penn Medicine analysis of more than 63,000 pregnancies from 2010-2017 found that with every 10% increase of Black people in a census track, severe maternal morbidity increased by 2.4%. Researchers pointed to several possible factors including greater exposure to environmental toxins, systemic racism, ongoing stressors caused by inequities and a lack of access to fresh produce and green space.

Digital health – another focus of the institute – encompasses a broad scope, including telemedicine, health information technology, wearable devices and personalized medicine.

In Philadelphia, telemedicine helped eliminate a racial health disparity during the COVID-19 pandemic, a Penn Medicine study showed. Black patients were just as likely to complete post-hospitalization follow-up visits during the first half of 2020 thanks to the widespread shift to telehealth.

The study found that Black patients’ visit completion rates jumped from 52% to 70%. White patients’ completion rates essentially remained the same, dropping from 68% to 67%.

But access to technology remains a barrier. White Philadelphia residents are far more likely to have a subscription to broadband internet than Black and Hispanic residents.

Colleen Claggett/For PhillyVoice

Colleen Claggett/For PhillyVoice

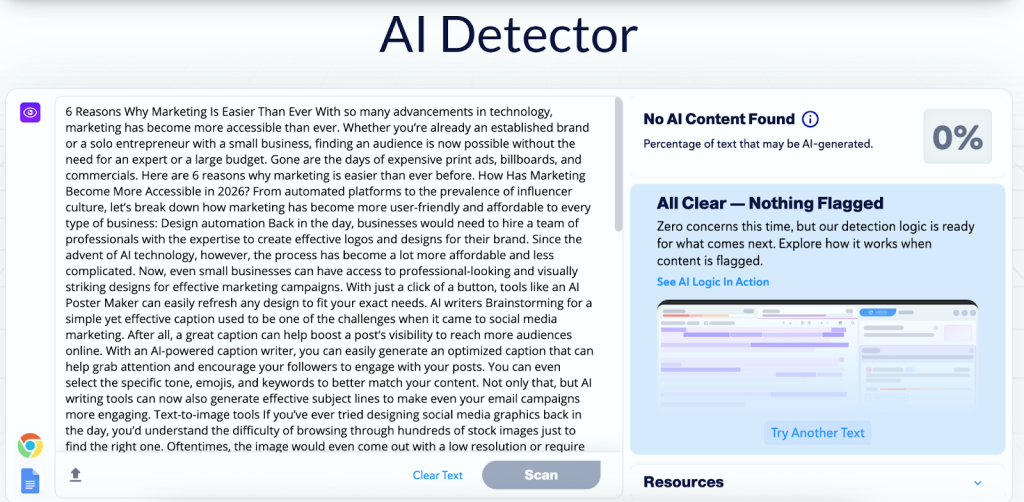

Independence Blue Cross President and CEO Gregory Deavens speaks at an event announcing the Institute for Health Equity, a program that aims to address health disparities in Philadelphia.

Other health conditions, including heart disease, colorectal cancer and diabetes, also are more prevalent among Philadelphia’s Black residents. And they’ve been been more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19 or die of it.

The city’s Black and Hispanic residents are far more likely to be uninsured than white residents. They’re also more likely to be obese, have limited access to healthy foods and live in poverty.

In light of these persisting health inequities, city health care leaders have taken recent steps to ensure all residents receive proper health care.

The Philadelphia Health Department has hired Gail Carter Hamilton as its first chief racial equity officer to help to address health inequities in the city and ensure the department’s operations are racially equitable.

Additionally, 10 Philadelphia area hospital systems, medical schools and health insurers – including IBC – have teamed with the city to address health inequities in the city through Accelerate Health Equity, an initiative to address 16 “health-equity challenge areas” which include heart disease, colorectal cancer, obesity, diabetes, housing and food access, community violence and the percentage of children living in poverty.

Now, the IBC Foundation has created the Institute for Health Equity as a way to mark its 10th anniversary. By the end of the year, the foundation will have awarded nearly $70 million in charitable grants to nonprofits and research efforts that analyze community health.

“Health equity is integral to our ongoing philanthropic commitment to improve the health and well-being of our community,” said Reverend Dr. Lorina Marshall-Blake, president of the IBC Foundation. “Through the institute, we will work collaboratively across sectors to leverage research, expertise, and invest our resources to be a national leader in improving the health of disadvantaged groups.”