“Sometimes people can feel vulnerable or embarrassed to be here, and I think it helps normalize the experience and tell them, ‘It is OK to seek help, it is OK to get the support you need,’” behavioral health consultant Ashley Ogden says. (Savannah Blake/The Gazette)

IOWA CITY — In the first year since the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics established behavioral health consultants with its inpatient psychiatric unit, providers have seen a “significant” reduction in patient crisis situations and overall improvement in patient experiences.

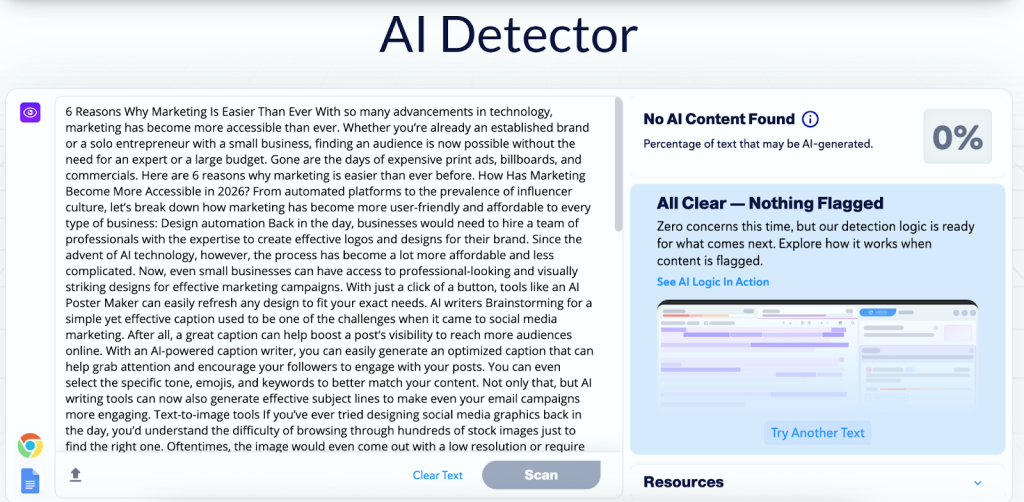

In an effort to meet increased patient demands and reduce length of stays, officials have hired these staff members, who do not have clinical degrees but have experience that enhances the health care system’s model.

According to preliminary data and anecdotal trends collected by providers, the team is accomplishing this goal.

The hospital deploys a team to help de-escalate the actions of a patient who is experiencing a behavioral health emergency.

Such an emergency is when a person is at risk of hurting themselves or others or their behavior prevents them from being able to care for themselves or function effectively in the community, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, an advocacy organization.

In the past year since behavioral health consultants began working in the psychiatric unit, the number of times this response team has been called has decreased, said Heidi Robinson, director of behavioral health services at UIHC.

“That’s ultimately led to the least restrictive outcomes for patients, which is excellent for patient care,” Robinson said. “It’s not traumatizing. It’s patient-focused, it’s patient-centered.

“And it’s fulfilling to staff, because staff can see that what they’re doing is working.”

The unit has also seen a decrease in staff injuries reportable to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, said Dr. Kelly Vinquist, clinical associate professor of psychiatry and co-director of the UI Intellectual Disability-Mental Illness Program.

Vinquist noted the data on hand is preliminary, as the behavioral health consultant program has evolved substantially over the past year.

What is a behavioral health consultant?

The UI Intellectual Disability-Mental Illness Program, a four-bed unit within the psychiatric unit, has employed a behavioral health consultant since 2015, Vinquist said.

The number of consultants was expanded in March 2021 when the hospital reopened its new remodeled inpatient psychiatric unit, located on the seventh floor of the Roy Carver Pavilion.

These individuals have bachelor’s degrees in special education, social work or psychology, and must have experience working with individuals with challenging behaviors.

The unit currently employs eight behavioral health consultants, Robinson said.

As they spend time with patients in their day-to-day line of work, these staff members share their observations to the care team to help inform providers’ treatment plans for each patient.

Ashley Ogden, who has a degree in social work, was among the first of three behavioral health consultants hired in March of last year. Before taking the role, Ogden spent more than six years working at a neurobehavioral rehabilitation facility for patients with brain injuries.

Ogden said she approaches her role with a person-first mentality that attempts to remove the stigma around seeking care for mental health.

“Sometimes people can feel vulnerable or embarrassed to be here, and I think it helps normalize the experience and tell them, ‘It is OK to seek help, it is OK to get the support you need,’” Ogden said.

Behavioral health consultants also are given specialized training by psychiatric providers in an effort to equip them with the most up-to-date techniques to prevent challenging behaviors.

Oftentimes, that means helping patients learn coping skills, Ogden said. For example, when patient in the unit’s eating disorder unit began having panic attacks for the first time, Ogden taught that individual breathing techniques and other steps to help carry them through those crisis moments.

“By doing that, we can decrease our length of stays and get them discharged,” Robinson said.

Vinquist said these staff also help identify patient needs and fill the gaps.

Providers noted patient mental health crises — called Code Greens — were more likely to happen in the evenings or on weekends, when there is less structure in the patient’s day. As a solution, behavioral health consultants started book clubs, yoga classes and activities during those periods, Vinquist said.

Overall, providers also have seen an improvement in patient satisfaction since the number of behavioral health consultants have been expanded on the unit, Vinquist said.

Meeting the rising needs

This move comes as the Iowa City-based hospital and other across the state are seeing a major spike in individuals seeking mental and behavioral health care after the COVID-19 pandemic, when many people were isolated, dealt with stress due to job loss or housing changes, and otherwise faced increased anxiety and depression in the past two years.

Not only are hospital officials seeing an overall increase in patients with mental health concerns, but providers also are seeing an increase in the number of patients seeking care during a crisis, the UIHC’s Robinson said.

Vinquist agreed, saying the overall severity of needs also has increased in recent years.

Long-term, Robinson said other officials hope to employ behavioral health consultants in other parts of the hospital to address needs of more patients. No plans have been made to do so in the immediate future, however.

“The pandemic has changed a lot of things, and it’s changed our health care delivery system,” Robinson said.

“I think it’s important as we move forward that we’re able to meet the needs of each other. And that comes with meeting the needs of our staff, our patients and our organizations.”

Comments: (319) 398-8469; [email protected]

Behavioral Health Consultant Ashley Ogden outside the University of Iowa Hospital in Iowa City on Wednesday. UIHC has reworked its behavior health care inpatient services after a need increased from the pandemic. (Savannah Blake/The Gazette)

Behavioral Health Consultant Ashley Ogden outside the University of Iowa Hospital in Iowa City on Wednesday. UIHC has reworked its behavior health care inpatient services after a need increased from the pandemic. (Savannah Blake/The Gazette)